An ongoing retrospective on the famous Indian sculptor sheds light on his life-like art and how, at 91, he is working on his tallest work so far.

Sculptures of Indira Gandhi, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in the lawns of a gallery in New Delhi that is hosting a retrospective on Indian sculptor Ram V. Sutar. He is best known for his life-like renditions of famous Indians.(Courtesy: Abhimanyu Jindal)

A statue with a face that is 70 feet high; and the retina alone is 6 feet in diameter. That is the staggering scale of the project that seeks to memorialise Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in cement, iron, steel and bronze. This towering monument to Patel, a leader of India’s nationalist movement and, later, its first deputy prime minister, is also known as the Statue of Unity. And the man who is designing it is Ram Sutar.

Ram Vanji Sutar, is probably, in a literal sense, the most showcased sculptor India has seen given that statues created by him adorn platforms across the country. And it’s perhaps owing to his unappealing dedication to the cult of personality in India’s history that Sutar’s own identity as an artist has escaped assessment. An ongoing retrospective on Sutar at the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS) seeks to address that.

Sutar, born in 1925 in Gondur, Maharashtra, to a carpenter, went to the Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai. At an early stage in his career, he was commissioned to assist in restoring statues in the Ajanta and Ellora caves; the figurative energy from which is visible in his sculptures displayed at AIFACS.

Alongside the busts of many of India’s leaders through history is a collection of Sutar’s drawings and paintings. These paintings, at the outset, reveal a man excavating mythology for inspiration and finding a kind of repose in the embrace of parenthood. Among Sutar’s mythological muses, Shiva and Saraswati appear repeatedly, with the former taking many incarnations. Most of Sutar’s “soft works” (drawings, paintings) are mannered to a predictable script, seldom exceeding that format in imagination. It is his sculptures that affirm the magnitude of his craft.

Indian sculptor Ram Sutar at his studio in Noida in 2009. Sutar, now 91 years old, is building a 395-foot-high statue of Maratha king Shivaji in Mumbai and a 522-foot-high statue of Sardar Patel in Gujarat. (HT file photo )

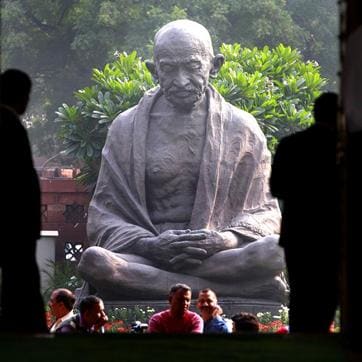

Magnitude is important here because Sutar’s oeuvre itself is a play on the idea of scale. Sutar has built giant statues: in his first celebrated work of Chambal, a 45-foot marvel he created in 1961 along the Gandhi Sagar Dam over the Chambal river, he depicted Chambal as the mother of the two states it flows through, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. At that scale, a statue becomes a monument. An artist working to that degree of scale is extremely difficult to showcase in a gallery. That said, there is plenty to go by in the form of the busts that Sutar has delivered from China to Belgium — downscaled models and large renditions of Indira Gandhi, Sardar Patel and Pandit Nehru in the lawn of the gallery itself.

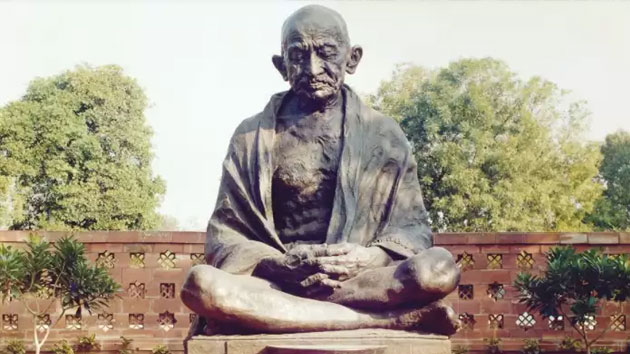

Mahatma Gandhi makes the most number of appearances (the statue of Gandhi in Parliament has been done by Sutar). In each of the faces, Gandhi’s as well as the others’, the quest for personality is apparent.

“We of course study the person,” says Anil Sutar, son of the now 91-year-old Ram Sutar, about the delicate process of getting to the face through the person. “We look at thousands of photographs of him or her from all angles and also study them at different moments of time, in different contexts, so we know what face to go with.”

Unlike paintings, these structures remain out there, in the public eye, probably forever. A frown here or a drooping eyelid there is, therefore, unpardonable, unless it’s called for.

The impressionist Auguste Rodin once said of sculpting that it is “the art of the hole and the lump”, indicating the extra dimension. Although geometric precision, in terms of length and breadth, is crucial, sculpting requires an eye trained to identify depth.

Sutar is now working on the mammoth 522-foot-high statue of Sardar Patel in Gujarat and on an equally challenging, though smaller, 395-foot-high Shivaji statue in Mumbai. “First we make a 3-ft model, then an 18-ft model and then a 30-ft model and so on. So we basically scale up,” says Anil.

The statue of Mahatma Gandhi in front of Parliament House in New Delhi is arguably Ram Sutar’s best known sculpture. Gandhi has been Sutar’s most common muse. (Sanjeev Verma/ HT Photo )

“You can imagine the size of the task,” he adds, referring to the magnitude of Patel’s statue. These will be visible from the sky, let alone in parkways or galleries where art is dissected along aesthetic lines.

Sutar is not an explorer. He is devoted more than he is dedicated. And in his work, his love of personality, and the weight of history that has shaped it, comes through. He is a patriot, and at the heart of each of his creations, he is reaching out to the patriot in us. It is more than just substantial when a gallery struggles to evoke the magnitude to which this icon of sculpting has worked.

At his age — 91 years — the ‘Statue of Unity’ may well become Sutar’s greatest legacy: a legacy he avowedly shares with his motherland and has distributed across the world. Outside, at the intersection of Raisina Road and Rafi Marg, opposite the AIFACS building, stands a statue of another nationalist leader, Govind Ballabh Pant. The sculptor? You guessed it.